By EmilyM

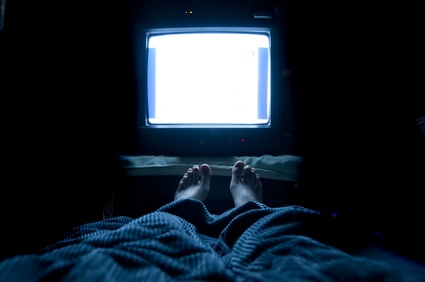

Many of us rely on the dim light and quiet hum of the TV to drift off into a peaceful slumber at night, but after hearing the results of this recent study we may want to consider this habit.

Many of us rely on the dim light and quiet hum of the TV to drift off into a peaceful slumber at night, but after hearing the results of this recent study we may want to consider this habit.

During a recent study in the effect of light on eating behavior and weight gain, it was discovered that mice exposed to light during periods of rest gained weight more frequently than those who rested in complete darkness.

The study was conducted by Laura K. Fonken, a graduate student at Ohio State University, in Columbus, and her colleagues and was recently reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

It may seem unlikely that light could have any bearing on weight, however, the proof seems the be in the study. Not only did the mice exposed to even dim light gain weight, but they also showed a reduced glucose tolerance. The strange part is that it didn’t appear the light-exposed mice were less active or even eating more, they were simply eating at strange, typically inactive, hours. Researchers compared this to the results of people habitually eating midnight snacks or late night meals.

The study researchers also pointed out why these seemingly unrelated things are in fact linked. The body is set by “clock genes” to maintain a certain schedule which is influenced by light exposure. These “clock genes” control our usual desire for things like sleep and food. When exposed to light during normal rest hours, these genes seem to be thrown off.

Researchers tested this out on three different groups of mice. The first group received the average 16 hours of daylight followed by 8 hours of darkness. The second group received 16 hours of daylight followed by 8 hours of dim light and the third group received 24 hours of bright light. The dim light used in the second group was meant to simulate the same lighting that would come from a TV screen.

One week into the study, it was already noticeable that the 2 groups who had been exposed to light during the ordinary dark nighttime hours were gaining weight. By the end of the study, 8 weeks later, there was a significant measurable difference in the groups of mice. The dim light group actually had a 50% greater increase in weight than the ordinary 16 hours of light and 8 hours of dark group. This may partially have come from the abnormal eating patterns observed in the animals during the typical daylight hours. Since mice are nocturnal, they typically do not eat much at all during the daylight hours. However, the groups exposed to both bright and dim light ended up eating far more than normal during the daytime.

In a second test, the mice were only offered food during their traditional eating hours at night. In this case, weight gain did not appear to be out of the ordinary. This further proved the study’s findings that it is the eating habits which are disrupted due to light at odd non-active hours that had been causing the metabolism to slow down and weight gain to occur.

Though it can not be positively inferred that the same results can be said for people, many speculate that there is a correlation between the reaction seen in mice and the impact dim light can have on humans during normal sleeping hours.